Turkey is no longer merely approaching a crisis—it has already crossed the threshold. What was once a troubled but functioning democracy is now a country that has fully embraced authoritarianism. The breaking point is not a future risk; it is the present reality. Repression is no longer creeping—it is galloping. With each passing day, Erdoğan's regime deepens its campaign to dismantle dissent, suppress civil liberties, and consolidate one-man rule, and in doing so, it reveals the fear and fragility underlying its grip on power. The system has lost the capacity for self-correction, and the damage to Turkey's institutions may already be irreversible. The repression has become not just relentless—it has become reckless. Worse, the cumulative effect of these developments is pushing Turkey dangerously close to the textbook definition of a failed state.

A failed state is not defined solely by the collapse of government institutions or open civil war. It is marked by the systematic erosion of the state’s core functions: the ability to govern legitimately, maintain internal order, deliver public services, uphold the rule of law, control its borders, and command the loyalty and confidence of its citizens. By these standards, Turkey is alarmingly far along the path of state failure.

Political repression in Turkey has reached unprecedented heights. The government is no longer satisfied with simply silencing critics—it is dismantling the very foundations of democratic governance. Opposition leaders, journalists, academics, union organizers, students, and even ordinary citizens are targets of constant surveillance, arbitrary detention, and politically motivated prosecutions. The judiciary has been stripped of independence. Courts are no longer instruments of justice but weapons of retaliation.

There is no single, universally agreed-upon definition of a "failed state." Still, most descriptions share a set of common and often interconnected features:

Weakened control over national borders: Parts of the country may fall under the control of criminal groups, rebel forces, or even foreign military powers.

Loss of internal security: The state can no longer maintain a monopoly on the use of force. Law enforcement weakens, crime rises, and public safety deteriorates.

Collapse of public services: Essential services, such as healthcare, education, infrastructure, policing, and firefighting, begin to break down or disappear.

Economic breakdown: High unemployment, runaway inflation, currency devaluation, and widespread corruption become the norm. Tax collection declines, and financial crimes go largely unchecked.

Erosion of legitimacy: Citizens and the international community lose faith in the government's competence and authority, often viewing it as ineffective or untrustworthy.

Together, these factors indicate a state that can no longer fulfill its basic governance functions, opening the door to chaos, fragmentation, and prolonged human suffering.

Not all failed states disappear. More stable countries take over, while others rebuild with stronger governments, and many continue to exist for years—sometimes for generations—despite worsening conditions for their people. Because there’s no official definition of a failed state, there’s also no agreed-upon list of which countries qualify. Some experts even argue that the concept itself is more political than factual.

Of the five core criteria commonly used to describe a failed state, Turkey now meets at least four by virtually any objective assessment. Beneath this political decay lies a deeper rot. The state has turned inward, treating its own citizens as if they were enemies. Police violence is rampant. Arbitrary searches and detentions are common. Ethnic minorities, especially Kurds, are systematically persecuted. Civil society is choked. Protesters are brutalized. Activists disappear into the penal system. The social contract has been shredded; the government does not protect—it punishes.

The economic situation mirrors this collapse. Inflation is out of control. Corruption is rampant. Capital is fleeing. Young professionals are emigrating in record numbers. Public services are eroding. Infrastructure is neglected. Hospitals and schools are under-resourced. The state can no longer meet the basic needs of its people, and increasingly, it no longer even pretends to try.

While Turkey still might possess the military capability to defend its borders against a foreign invasion, it has failed to control its borders effectively in peacetime, particularly when it comes to managing refugee flows and extremist infiltration. For years, jihadists, smugglers, and traffickers moved freely across its southern frontier. The country has absorbed millions of refugees without a coherent policy. Border control has become both a humanitarian disaster and a geopolitical bargaining chip. This is not the behavior of a sovereign state confidently in control of its territory. This breakdown of border integrity underscores a broader governance crisis and challenges the notion that Turkey remains a strong, sovereign state in full control of its territory.

Even Turkey’s armed forces, once regarded as the most disciplined and professional institution in the country, have not been spared from politicization and decay. Following the mass purges after the 2016 coup attempt, thousands of experienced officers were dismissed and replaced with political loyalists. The chain of command has been reshaped to serve the regime rather than the nation. As a result, basic operational standards have deteriorated. The tragic death of 12 soldiers from methane gas poisoning in a cave during what was meant to be a routine operation is a glaring example. In any competent military, such an avoidable disaster would spark outrage and accountability. In Erdoğan’s Turkey, it is met with silence and spin. The armed forces, like every other institution, have been hollowed out in the name of loyalty.

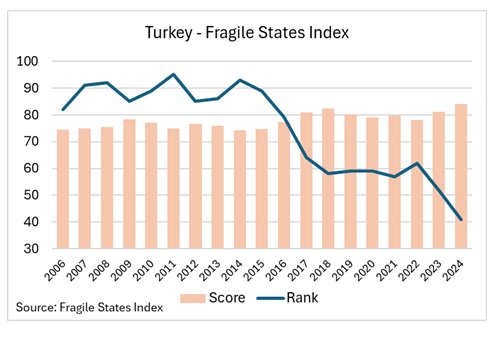

One of the most widely used tools to assess state fragility is the Fragile States Index (FSI), created by the non-profit Fund for Peace. It evaluates countries across 12 key areas—including security, economy, public services, and rule of law—based on over 100 data points. Each country receives a score from 0 (most stable) to 120 (most fragile). While the FSI doesn’t define a clear line between "fragile" and "failed," countries scoring 60–89 receive a warning, and those scoring 90 or above are considered at high risk of collapse.

Turkey’s score on the Fragile States Index (FSI) has been steadily increasing in recent years, indicating a rise in internal fragility across areas such as governance, public services, and economic stability. At the same time, its rank from the bottom has been declining, meaning it is moving closer to the most fragile countries in relative terms. This dual trend suggests that not only are Turkey’s internal conditions worsening, but its global standing is also deteriorating compared to other countries, especially in recent years, as reflected in the data.

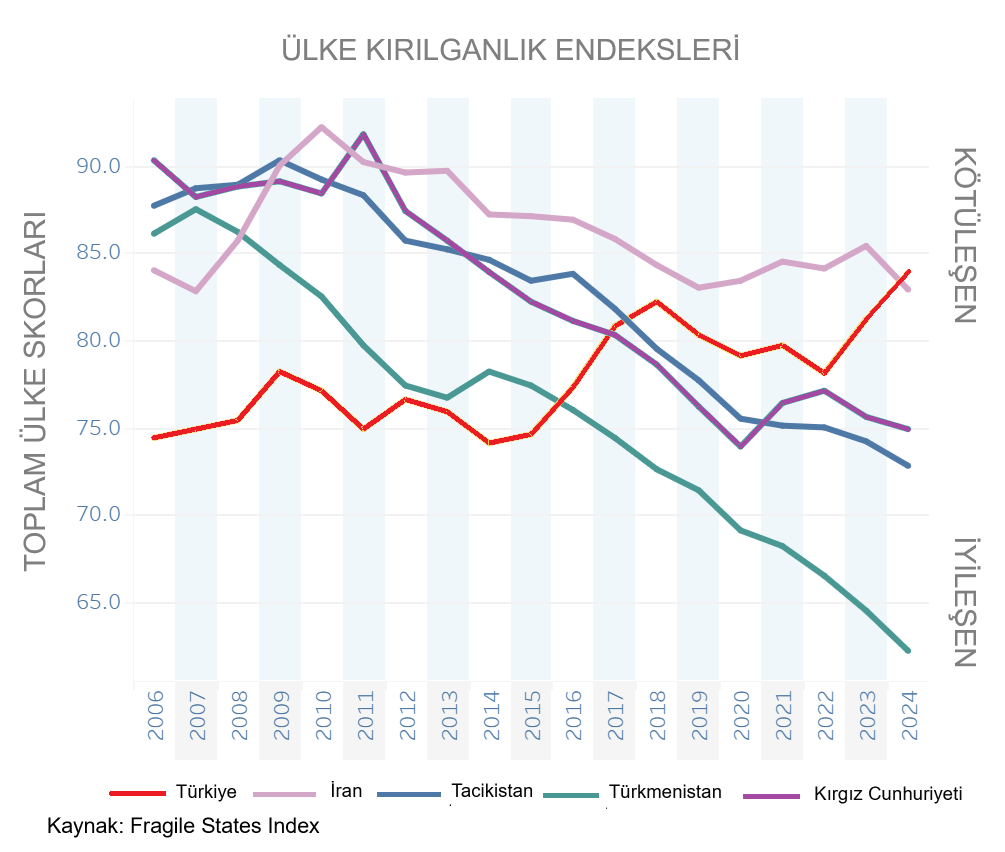

The following chart compares Fragile States Index (FSI) scores from 2006 to 2024 for five countries: Turkey, Iran, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Kyrgyzstan. A higher score reflects greater fragility, while a lower score indicates a more stable and resilient state. The overall trends show diverging paths across the region.

While some Central Asian countries have made steady progress toward greater stability, Turkey stands out as an exception, with its fragility having worsened sharply over the past decade. This trend is particularly striking given the historical context: Thirty years ago, Turkey often positioned itself as the “big brother” to the newly independent Central Asian republics, offering a model of democracy, secular governance, and economic reform. Yet today, many of those same countries—despite being ruled by authoritarian regimes—have managed to reduce their fragility scores, while Turkey has moved in the opposite direction. The reversal highlights not only Turkey’s internal deterioration but also the shifting balance of political and institutional resilience in the region.

And yet, none of this signals strength. On the contrary, Erdoğan’s increasing repression is a sign of panic and fear. The regime is not projecting confidence; it is flailing. Like many autocracies before it, it has confused control with stability and fear with loyalty.

History teaches us that authoritarian regimes often collapse under the weight of their own contradictions. They may appear stable—until, suddenly, they are not. The stories of Marcos in the Philippines, Ceaușescu in Romania, Akayev in Kyrgyzstan, Mubarak in Egypt, Ben Ali in Tunisia, and Assad in Syria, whose refusal to reform plunged his nation into civil war, all serve as stark warnings. Each ruler relied on fear, patronage, and repression, believing in the illusion of invincibility. But when their own people rose up, the regimes unraveled with astonishing speed.

The public’s patience is wearing thin. As CHP leader Özgür Özel recently warned, the mass protests his party has begun organizing are merely “trailers” for what’s to come. The Turkish people are not indefinitely pliable. If the government continues on this path of repression, economic hardship, and contempt for the will of the people, a historic confrontation becomes inevitable. Two million protestors standing in front of Erdoğan’s palace is no longer an impossible image; it is a plausible scenario.

Such a moment could lead to chaos, even bloodshed. However, it may also mark the end of Erdoğan’s sultanate-in-the-making. The more brutally he clings to power, the more likely he is to be consumed by the very storm he provokes.

The international community must stop viewing Turkey merely as an “illiberal democracy” or a “flawed ally.” It is a country on the edge of systemic collapse. Either it will rediscover the democratic values that once gave it hope, or it will slide further into dysfunction, repression, and possibly irreversible decline.

And it is now too late for the former.

What lies ahead is not reform, but reckoning. The system Erdoğan has built—founded on fear, propaganda, and the dismantling of institutions—is beyond repair. The collapse, when it comes, will be turbulent. The question is not if it happens, but how much damage the country will endure on the way down—and whether those who survive it can build something better from the ruins.

Tragically, this is not a uniquely Turkish trajectory. The United States itself is moving in the same direction, with determined steps. Under Donald Trump’s increasingly autocratic influence, American democracy is being hollowed out from within. The erosion of judicial independence, the normalization of political violence, the dismantling of institutional guardrails, and the use of state power for personal vendettas are no longer hypothetical risks—they are visible realities.

The parallels are striking. In both countries, we see the cult of personality replacing political accountability. We see the courts weaponized, the media delegitimized, and truth itself under siege. We see elections transformed from democratic exercises into manipulated rituals. The danger is not just authoritarianism—it is systemic failure, from which recovery may not be guaranteed. What is unfolding in Turkey today may well be a warning for America tomorrow.

The death of democracy is rarely sudden—it arrives slowly, deliberately, and often under the cover of legality. By the time the collapse becomes visible, the foundations have already been hollowed out. If we fail to confront this erosion while there is still time, we will find ourselves not at the ballot box, but behind bars, demanding what is rightfully ours: our freedom and our rights.

Çöküşteki Devlet

Türkiye artık bir krizin eşiğinde değil—o eşiği çoktan aştı. Bir zamanlar sorunlu ama işleyen bir demokrasi olan ülke, bugün tam anlamıyla otoriterliğe teslim olmuş durumda. Kırılma noktası artık gelecekteki bir risk değil; bugünün gerçeği. Baskı artık yavaş yavaş ilerlemiyor—adeta koşar adım geliyor. Her geçen gün Erdoğan rejimi, muhalefeti bastırma, sivil özgürlükleri yok etme ve tek adam iktidarını pekiştirme kampanyasını daha da derinleştiriyor ve bu süreçte iktidarını ayakta tutan korku ve kırılganlığı da açık ediyor. Sistem kendi kendini onarma kapasitesini yitirmiş durumda ve Türkiye’nin kurumlarına verilen zarar artık geri döndürülemez bir boyuta ulaşmış olabilir. Daha da kötüsü, bu gelişmelerin birikimli etkisi Türkiye’yi klasik anlamda bir “Failed state” tanımına tehlikeli biçimde yaklaştırıyor.

“Failed state” teriminin Türkçeye çevrilmesi bağlama göre değişir. En yaygın karşılığı “Başarısız Devlet” olsa da, “Çökmüş Devlet”, “İflas Etmiş Devlet” ya da “Çöküşteki Devlet” gibi tanımlar da kullanılabilir. Bu yazıda, henüz tamamen çökmemiş ancak yapısal krizler, ekonomik istikrarsızlık, yolsuzluk ve kamu hizmetlerinde aksaklıklar gibi sorunlarla derinleşen bozulma sürecini tanımlayan “Çöküşteki Devlet” terimini kullanacağız.

Başarısız bir devlet yalnızca kurumların çökmesi ya da iç savaşla tanımlanmaz. Devletin temel işlevlerinin sistematik biçimde aşınmasıyla tanımlanır: Meşru yönetim kapasitesi, iç güvenliğin sağlanması, kamu hizmetlerinin verilmesi, hukukun üstünlüğünün korunması, sınırların denetlenmesi ve halkın güven ve sadakatinin kazanılması. Bu ölçütlere göre Türkiye, devlet çöküşü yolunda endişe verici derecede ilerlemiş durumdadır.

Türkiye’de siyasal baskı eşi görülmemiş seviyelere ulaştı. Hükümet artık yalnızca muhalifleri susturmakla yetinmiyor—demokratik yönetişimin temelini de yıkıyor. Muhalefet liderleri, gazeteciler, akademisyenler, sendikacılar, öğrenciler ve sıradan vatandaşlar sürekli gözetim, keyfi gözaltı ve siyasi saikli davaların hedefinde. Yargı bağımsızlığı fiilen yok edilmiş durumda. Mahkemeler artık adaletin değil, intikamın aracı haline getirildi.

Çöküntüdeki devlet kavramının üzerinde evrensel bir uzlaşı olmasa da, çoğu tanım ortak ve birbiriyle bağlantılı unsurları içerir:

Zayıflayan sınır kontrolü: Ülkenin bazı bölgeleri suç örgütlerinin, isyancı grupların ya da yabancı güçlerin kontrolüne girebilir.

İç güvenlik kaybı: Devlet, silahlı güç kullanımı üzerindeki tekelliğini kaybeder; kolluk kuvvetleri zayıflar, suç artar, kamu güvenliği çöker.

Kamu hizmetlerinin çöküşü: Sağlık, eğitim, altyapı, polis ve itfaiye gibi hizmetler aksar ya da tamamen ortadan kalkar.

Ekonomik çöküş: Yüksek işsizlik, hiperenflasyon, para biriminin değer kaybı, yolsuzluk ve vergi toplayamama yaygın hale gelir.

Meşruiyetin erozyonu: Vatandaşlar ve uluslararası toplum, devletin meşruiyetine ve yetkinliğine olan güvenini kaybeder.

Bu unsurlar bir araya geldiğinde, devletin temel görevlerini yerine getiremediği ve toplumun kaosa, parçalanmaya ve uzun süreli insanî krizlere sürüklendiği bir tablo ortaya çıkar.

Başarısız devletler mutlaka ortadan kalkmaz. Bazıları dış güçlerce kontrol altına alınır, bazıları yeniden inşa edilir, bazılarıysa halkı için giderek kötüleşen koşullara rağmen yıllarca—hatta kuşaklar boyunca—varlığını sürdürür. Kavramın resmî bir tanımı olmadığı gibi, hangi ülkelerin bu kategoriye girdiği konusunda da uzlaşı yoktur. Bazı uzmanlara göre “başarısız devlet” kavramı zaten teknik değil, siyasidir.

Bu beş temel ölçütün dördü Türkiye için artık rahatlıkla geçerlidir. Bu siyasi çürümenin altında daha derin bir çöküş yatmaktadır. Devlet, yurttaşlarına hizmet eden değil, onları düşman olarak gören bir yapıya bürünmüştür. Polis şiddeti sıradanlaşmıştır. Keyfi gözaltılar, ev baskınları yaygındır. Özellikle Kürtler başta olmak üzere etnik azınlıklar sistematik biçimde hedef alınmaktadır. Sivil toplum boğulmakta, protestocular şiddetle bastırılmakta, aktivistler ceza sisteminde kaybolmaktadır. Toplumsal sözleşme ortadan kalkmış; devlet koruyan değil, cezalandıran bir mekanizmaya dönüşmüştür.

Ekonomik tablo da siyasi çöküşü yansıtmaktadır. Enflasyon kontrolden çıkmıştır. Yolsuzluk yaygındır. Sermaye ülkeden kaçmakta, genç profesyoneller kitlesel biçimde göç etmektedir. Kamu hizmetleri çürümekte, altyapı ihmal edilmekte, hastane ve okullar kaynak sıkıntısı çekmektedir. Devlet, halkın temel ihtiyaçlarını karşılayamamakta ve bunu artık gizleme gereği bile duymamaktadır.

Türkiye dış saldırılara karşı ordusunu harekete geçirebilecek kapasitede olabilir, ancak barış zamanında sınırlarını kontrol etmekte açıkça başarısız olmuştur. Yıllardır cihatçılar, kaçakçılar ve insan tacirleri güney sınırlarından serbestçe geçmiştir. Milyonlarca mülteci plansız biçimde ülkeye alınmış, bir yandan insani kriz yaşanırken diğer yandan sınır politikası dış ilişkilerde pazarlık unsuru haline gelmiştir. Bu tablo, egemenliğini ve sınırlarını etkili şekilde kontrol eden bir devletin görüntüsü değildir.

Bir zamanlar Türkiye'nin en profesyonel ve disiplinli kurumu olarak kabul edilen silahlı kuvvetler dahi bu çöküşten nasibini almıştır. 2016 darbe girişiminin ardından gerçekleştirilen büyük tasfiyelerle binlerce deneyimli subay görevden alınıp, yerlerine rejime sadık isimler getirilmiştir. Komuta zinciri artık devlete değil, Erdoğan’a hizmet eder hale gelmiştir. Bu da operasyonel standartlarda ciddi bir düşüşe yol açmıştır. Rutin bir görevde 12 askerin bir mağarada metan gazı zehirlenmesi sonucu hayatını kaybetmesi bunun çarpıcı örneğidir. Ehliyetli bir orduda bu tür bir skandal soruşturmalara ve istifalara neden olurdu. Erdoğan’ın Türkiye’sinde ise sadece sessizlik ve yalan vardır.

Devlet kırılganlığını ölçmekte kullanılan en yaygın araçlardan biri olan Fragile States Index (FSI) ya Kırılgan Devletler Endeksi, Türkiye’nin bu alandaki düşüşünü yıllardır açıkça göstermektedir. Güvenlik, ekonomi, kamu hizmetleri ve hukukun üstünlüğü gibi 12 başlık altında yapılan değerlendirmeler Türkiye’nin hem iç kırılganlığının arttığını, hem de dünya sıralamasında giderek daha alt sıralara düştüğünü ortaya koymaktadır.

2006’dan 2024’e kadar olan FSI verileri incelendiğinde, Türkiye’nin hem İran, hem Orta Asya’daki bazı otoriter rejimler karşısında dahi daha kırılgan bir duruma düştüğü görülmektedir. Oysa bundan otuz yıl önce, Türkiye bu ülkelere “büyük abi” rolüyle örnek bir demokrasi, laiklik ve ekonomik reform modeli sunmaktaydı. Bugün ise roller tersine dönmüş durumda.

Ve tüm bunlar bir güç göstergesi değil. Tam tersine, Erdoğan’ın baskıyı artırması panik ve korkunun dışavurumudur. Rejim artık özgüven yaymıyor; yalpalıyor. Daha önce nice otokrasi gibi, Erdoğan da denetimi istikrarla, korkuyu sadakatle karıştırıyor.

Tarih, otoriter rejimlerin çoğu zaman kendi çelişkilerinin yükü altında çöktüğünü gösterir. Dışarıdan bakıldığında güçlü ve kalıcı görünürler—ta ki bir gün birdenbire dağılana kadar. Marcos (Filipinler), Çavuşesku (Romanya), Akayev (Kırgızistan), Mübarek (Mısır), Bin Ali (Tunus) ve Beşar Esad (Suriye) örnekleri, halk desteğini kaybeden ve reformu reddeden liderlerin nasıl yıkıldığını çarpıcı biçimde ortaya koyar.

Halkın sabrı tükeniyor. CHP lideri Özgür Özel’in dediği gibi, partisinin organize ettiği protestolar “yalnızca fragmanlar.” Gerçek gösteri yolda. Erdoğan iktidara sarıldıkça, onu devirecek olan halk dalgası daha da büyüyor. Cumhurbaşkanlığı Sarayı önünde toplanacak iki milyonluk bir kalabalık artık hayal değil, ihtimal dahilinde.

Bu süreç kaos ve kan dökülmesine yol açabilir. Ama aynı zamanda Erdoğan’ın sultanlık hayalinin sonunu da getirir. Güce ne kadar çok sarılırsa, o kadar hızla çöküşe sürüklenecek.

Uluslararası toplum, Türkiye’yi hâlâ “kusurlu demokrasi” ya da “problemli müttefik” gibi etiketlerle tanımlamaktan vazgeçmeli. Türkiye artık sistemsel çöküşün eşiğinde bir ülkedir. Ya bir zamanlar umut veren demokratik değerlere geri dönecek—ya da bozulma, baskı ve belki de geri döndürülemez bir çöküş yoluna girecektir.

Ve artık geri dönüş için çok geç.

Bu rejimin gidişatı reformla değil, hesaplaşmayla sonuçlanacaktır. Erdoğan’ın inşa ettiği sistem—korku, propaganda ve kurumsal çöküş üzerine kurulmuştur—onarılmaz durumdadır. Tam çöküş geldiğinde sarsıcı olacak. Asıl soru şudur: Türkiye bu düşüşten ne kadar yara alacak—ve ayakta kalabilenler bu enkazdan daha iyi bir gelecek kurabilecek mi?

Üstelik bu yalnızca Türkiye’ye özgü bir trajedi değil. Amerika Birleşik Devletleri de benzer bir yola girmiş durumda. Donald Trump’ın otoriterliğe kayan etkisiyle Amerikan demokrasisi içten içe oyuluyor. Yargı bağımsızlığı erozyona uğruyor, siyasi şiddet normalleşiyor, kurumlar çözülüyor, devlet gücü kişisel intikam aracı olarak kullanılıyor.

Paralellikler çarpıcı. Her iki ülkede de siyasi hesap verebilirliğin yerini şahsi lider kültü alıyor. Medya düşmanlaştırılıyor, yargı silah haline getiriliyor, hakikat yok ediliyor. Seçimler artık bir demokrasi şöleni değil, manipüle edilmiş tiyatrolara dönüşüyor. Tehlike yalnızca otoriterlik değil—sistemsel çöküştür. Ve bu çöküşten geri dönüş her zaman mümkün değildir. Bugün Türkiye’de yaşananlar, yarın Amerika’ya gelebilecek olanın habercisidir.

Demokrasinin ölümü çoğu zaman ani değil, yavaş ve kasıtlıdır—üstelik çoğu zaman hukukun kılıfı altında gerçekleşir. Çöküş gözle görülür hale geldiğinde, temeller zaten içten içe çürümüş olur. Eğer bu çürümeye zamanında karşı çıkmazsak, o gün geldiğinde, kendimizi sandık başında değil, demir parmaklıklar ardında özgürlüğümüzü ve haklarımızı talep eder halde bulabiliriz.